- Annika Hansteen-Izora

- Jan 14, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 16, 2021

This piece was originally shared on my newsletter. If you’re committed to thoughtfully and intentionally supporting my work, please subscribe and read it here.

So much of the work of oppression is policing the imagination. Saidiya Hartman

It’s important for me to always start by naming where I come from, to give context to my relationship with dreaming, and to give you - the audience - agency in deciding if I’m someone you want to be hearing from. I’m a bi-sexual, queer, genderfluid, bi-racial, Black writer, whose dreaming practice is informed by Black Feminist Thought, Black Speculative Arts, design + AI justice, Afrofuturism, emergent strategy, glitch feminism and disability, healing, and queer & trans justice. In my practice, dreaming arises out of a desire to stretch towards speculative futures that exist outside of dominant forms of power, and to root in deep and ancient ancestral knowledge as a method of healing.

I grew up in East Palo Alto and the suburbs of Elk Grove, California, and Portland, Oregon, where I met tensions in being raised by fam that was deeply rooted in Black arts and technology, while attending predominantly white institutions from elementary to college. To use language from Claudia Rakine, I witnessed how Blackness in the white imagination has nothing to do with Black people. Whiteness is not just a race, it’s also a culture of supremacy. From white imagination comes systems and behaviors of domination and violence that we are not only forced to live with as normalcy, but also as something to aspire to.

Dreaming asks me to train my attention to constantly critique the white imagination, to be disenchanted by it, bored of it - to ask of something beyond its violent limits. Dreaming asks me to re-educate myself on its radical potential.

Duke Ellington on dreaming

A part of that re-education involves the naming names. It’s important for me to name that I am both an individual and a multitude. I’m a multitude because I am channeling the knowledge of people that came before me, whose dreaming allowed me to be here. I am a multitude in that I have the responsibility to honor the knowledge of those that have allowed me to be here.

As Audre Lorde said “There are no new ideas, just new ways of giving those ideas we cherish breath and power in our own living,” which is one of the centerfolds of Black feminism. Black feminism teaches us that we are multitudes of the knowledge, dreams, and actions of those that came before us.

The freedoms that I hold, that you hold, that we hold today, are because of the lineages of Black, Indigenous, POC, those with experiences in womanhood, sick and disabled, working class or poor, queer and trans genius that dreamed us into existence.

Those that came from these experiences looked at dominant narratives, and asked for a future where more was possible. They broke the mirror, and imagined possibilities of freedom beyond what they’d been handed by dominant systems. And they wove that knowledge into writing, songs, zines, videos, artwork, quilts, digital gardens, and other forms of creation so that it could be here for the future.

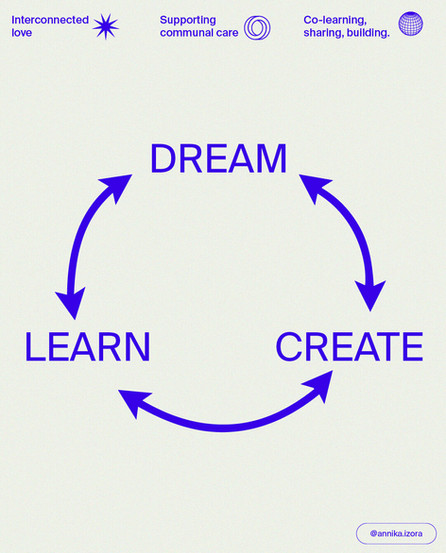

In this way, dreaming is a form of time travel. It is a seed rooted in the past, nurtured in the present, and looks towards possibilities in the future.

The way dreaming has been cultivated by Black feminism, Black radicalism, Indigenous activism, disability justice, and many other movements against the status quo, is that to dream is not just about helping one person be free, it is about freeing all of us.

The power of dreaming is in expansion. It allows us to expand beyond the confines of what has been handed to us as normalcy. What is considered normal is often defined (through violence and subjugation), by those that are in power. We live in a white, capitalist, colonialist, abeliest patriarchy society. And this society has allowed certain modes of violence to become normalcy. Daily, we witness incidents of racism, transmisogyny, abelism, colonialism, colorism, classism, whorephobia, and other modes of violence.

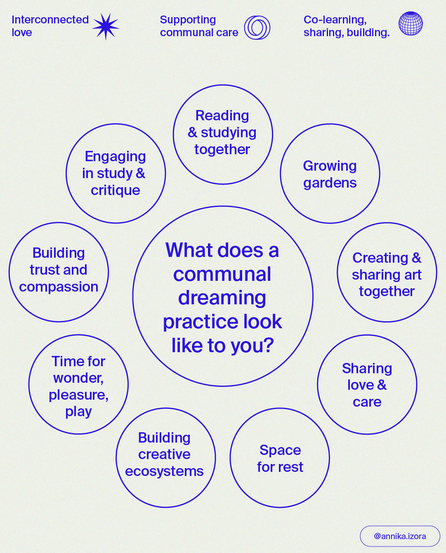

Dreaming is about expanding our minds beyond the culture of white supremacy, and the perfectionism, hyper-individuality, rushedness, and passiveness it sees as normal. It asks us to see our connections to each other, and to tend to and grow those connections to build structures outside of the tables that were never built with care in mind.

The Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist lesbian socialist organization, said: “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” The Combahee River Collective gives name to the ways in which our dreams are interconnected. We are multitudes. And this is the power in not only individually dreaming, but in collectively dreaming. There is power in communing in ideas of freedom that whiteness could never even fathom.

We see the power of collective dreaming in the calls for abolition, Black trans and queer leadership, disabled justice, Indigenous activism, Black Feminism, and every articulation of movement against the status quo. In her essay Poetry is Not a Luxury, Audre Lorde said, “Within structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive. Kept around as pleasant pastimes...But poets have survived. There are no new pains. We have felt them all already. We have hidden that fact in the same place where we have hidden our power. They lie in our dreams, and it is our dreams that point the way to freedom. If what we need to dream, to move our spirits most deeply and directly toward and through promise, is discounted as a luxury, then we give up the core -- the fountain -- of our power...we give up the future of our worlds.” I want to name that piece of knowledge, because what I do not intend to do here is to romanticize dreaming. Communal dreaming cannot become a trite bumper sticker splayed on the instagrams of wealth, education, white-proximate privileged people to perform wokeness. I understand romanticization as dislodging purpose, intention, and history from a concept. In the age of the internet, we see the consequences of romanticization everywhere, from those that see last week’s intentional power grab by white supremacist investors as nothing more than an unorganized mob, to dislodging community, or making a practice communal, from the radical roots from which it comes and the intentional and repeated actions it calls for in its maintenance. I am constantly amazed and taught by Tricia Hersey of the Nap Ministry’s supreme commitment to making sure the radical knowledge of rest as a site of liberation is not washed by romanticization. Communal dreaming cannot be romanticized. It is an act that asks us to fight against the white, capitalist, colonialist, abeliest patriarchy. Communal dreaming means committing to reindigenization, which as Neema Githere articulates, involves, “(1). abandoning the ideals and systems established through colonization [and] (2.) An evolution towards-and rememory of - ancient modes of knowledge and community.” This is deep work that involves daily practice. In dreaming I am constantly brought back to the work of Mandy Harris Williams, who has spoken fervently about how our “attention is a muscle” that requires training and commitment.

Showing up for dreaming means we must embrace a culture of learning that sees the values in different strategies, resources, and tools that each of us bring to the table. As those in the disability justice movement have taught us, movement work insists that none of us are left behind. Communal dreaming means fighting for each other to have the right to dream. It means building networks and structures that serve us and our right to agency and safety.

Many of us do not have the resources or stability to dream. The space to dream is a privilege in and of itself. To have space to dream, we need rest, food, shelter, health care, access to resources that allow us agency. Gloria Steinmen said, “Dreaming, after all, is a form of planning.” How can we dream new systems that don’t use people’s spare time to plug the gaps left open by neoliberalism? How can we dream slowly and sustainably? How can we dream in ways that don’t recreate the behaviors of the systems we want to abandon - like burnout, defensiveness, or passivity?

Rudolf Steiner, Human and Cosmic Thought

Over decades, we’ve watched government systems cut funding and initiatives for education, the arts, healthcare, care work, affordable housing, and community programs that could lead us to an abolition of our prison system. Making space to dream means looking at the entire picture, the individual, the communities, and the structures in which everything lives. It means thinking, and implementing, sustainable structures that allow each of us the capacity to care for ourselves and each-other, and thus the space to dream. Systems rooted in accountability, interdependence, communal care, and love.

I want to underscore that communal care is neither simple, not the sole solution to our problems. Community, like gardens, get messy as their nature. As I’ve learned from the work of Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, for many of us, receiving care is frightening because we’ve been in situations where care is violent or conditional. Making space to dream together must recognize the impacts of trauma, especially as marginalized people. Many of us may have a hard time in sharing our dreams with others, because dream-sharing is a vulnerable act. Sharing vulnerability may incite fear for those that hold trauma with it.

Shoutout to the teachers and visionaries whose work went into the creation of this piece and that continue to teach me about dreaming: Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King Jr., Octavia E. Butler, Audre Lorde, Robin D.G. Kelley, Tricia Hersey x The Nap Ministry, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Neema Githere, Mandy Harris Williams, Tricia Hersey, Decolonize the Art World, Terry Marshall, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Tourmaline, adrienne maree brown, Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun, and countless others.

For more resources on Communal Dreaming, visit my Communal Dreaming Are.na Board.

zodiakslot login

zodiakslot

situs slot online

Slot Resmi Server Thailand

slot88 resmi login

slot gacor hari ini

mesin slot gacor

Elevate your rummy game with Rummy Perfect – where strategy meets precision.